In 2018, two major hurricanes, Florence and Michael, crossed over the southeastern United States. They caused considerable damages state-wide, costing over $23 billion in North Carolina alone. Storm surges, rain, and high winds negatively affected historic structures and archaeological sites.

In response, Congress approved the Emergency Supplemental Historic Preservation Fund (ESHPF) grants. The National Park Service administers these grants. North Carolina received $17 million from ESHPF. These grants help communities repair historic buildings and prepare for future storm events. Local preservation groups and state agencies are eligible for funding.

The NC Office of State Archaeology received two of these ESHPF grants to support historic preservation projects. One of these projects is the North Carolina Shorescape Survey. This survey will assessed storm-related threats to shoreline sites in 12 coastal counties. Archaeologists identified important sites on land, underwater, and in the tidal zone. They also mapped the shoreline, which can change after every storm event. Prioritized survey areas included the African American and American Indian experiences in coastal North Carolina. Maritime industries from the 18th century to the present were also studied. We hope to identify and preserve sites not yet in the archaeological record!

The results of these surveys will guide plans to protect sites during storm events. They will also foster public education and the nomination of sites to the National Register of Historic Places.

How are we documenting our shorelines and shoreline sites?

Coastal North Carolina boasts a diverse environment, hosting numerous archaeological and historical sites that offer insights into the rich history of the state. Many of these sites are situated along our shorelines in the Coastal Plain, areas subject to continuous transformation, which can be further accelerated during severe weather events like Hurricanes Florence and Michael, which struck North Carolina in 2018. To understand the dynamics of these shorelines and the condition of the sites along them, we utilize a combination of methods to identify, document, and assess both site and shoreline stability within our project areas.

Prioritizing State-Owned and Managed Lands

Before commencing fieldwork, it is important to establish a systematic method for pinpointing the areas affected by Hurricanes Florence and Michael. We initiated this process by identifying Managed Areas designated by the NC Natural Heritage Program. Within the twelve project counties (Beaufort, Bertie, Brunswick, Carteret, Craven, Dare, Hyde, New Hanover, Onslow, Pamlico, Pender, and Tyrrell counties), we focused on state-owned and managed lands. These properties underwent further evaluation based on their environmental and historical significance.

The environmental priority of each property was determined by assessing the extent of flooding and the types of sediments in the area. We estimated flooding, or storm inundation, caused by both Florence and Michael using Category 4 Hurricane storm surge levels in the SLOSH Model, provided by NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. Sediment data was sourced from geological maps from the NC Department of Environmental Quality, with particular emphasis on sediments prone to erosion.

The historical priority of each property was determined by examining previously documented archaeological and historical remains, as well as evaluating the likelihood of undiscovered sites. This assessment drew upon a range of data sources, including the locations of previously recorded pre- and post-contact archaeological sites, historic maps delineating plantations and maritime infrastructure, and archival documents discussing the locations of fishing, shipbuilding, and maritime industries and infrastructure.

For each property, environmental and historical priority were assigned a numerical value between 0 and 5, with 0 denoting the lowest priority and 5 indicating the highest priority and, consequently, the highest level of risk. Properties with high scores in both categories were considered for fieldwork. The selected areas for this project include Hammocks Beach State Park in Onslow County, the Alligator River Game Land in Tyrrell County, and the Scuppernong River Section of Pettigrew State Park Dedicated Nature Preserve in Tyrrell County. Learn more about these locations!

Terrestrial Survey

Terrestrial surveying techniques were employed to identify, document, and assess shoreline sites located a minimum of 60 meters (approximately 200 feet) inland from the high tide line in each priority area. Each survey consisted of two components – a pedestrian survey and a shovel test survey.

During the pedestrian survey, archaeologists walked, waded, or snorkeled in shallow waters to identify artifacts and features visible on the ground surface. All identified artifacts and features were photographed, recorded, and mapped.

Shovel test surveys were conducted over the same area as the pedestrian survey, following a systematic survey approach. Archaeologists excavated 1-meter deep holes to ascertain the presence of buried artifacts or features. These pits were dug where the water table was at least 1 meter deep, as pits in shallower areas would simply fill with water. After completing each shovel test, the soil profiles of the pit wall and any artifacts were photographed, recorded, and mapped.

Underwater Survey

To complement the terrestrial survey, an underwater survey was conducted in the waterways adjacent to the surveyed land, with the aim of identifying sites that are already submerged along the shoreline. These surveys utilized remote sensing tools, including a magnetometer, a side scan sonar, and a sub-bottom profiler, to identify cultural resources.

The magnetometer identifies anomalies that may be located on or under the seafloor by measuring variations in the Earth’s magnetic field. The Earth’s magnetic field is consistent for any given location; when the magnetic field deviates from the expected, an anomaly is identified. These anomalies indicate the presence of a magnetic object, typically made of iron, such as a shipwreck or associated materials like a cannon.

The side scan sonar creates an image of the seafloor using sound. On either side of the device, there are transducers that emit sound waves into the water. These waves travel through the water, bounce off objects they encounter, and return to the device. Based on the time it takes for the sound waves to return, an image of the seafloor is produced. This allows archaeologists to identify cultural materials on the seabed and obtain certain characteristics of these sites, including how much is exposed above the sand.

Similar to the side scan sonar, the sub-bottom profiler also uses sound to image the seafloor. Instead of focusing on the surface, the sound waves penetrate the seafloor to create an image of the buried environment. While it can be used to identify cultural materials, this device is primarily employed to identify past geological and sedimentary characteristics, producing images of previous floodplains and coastal landscapes.

Shoreline Erosion Analysis

To better understand how shoreline sites are being affected by shoreline change, a two-step approach was employed to characterize the shorelines. Initially, while in the field, archaeologists recorded tidal levels for both high and low tides along the entire extent of shorelines in the project areas. Additionally, they took photographs of the full shorelines to categorize areas experiencing erosion, accretion, and stability.

Subsequently, the team utilized the field data and conducted an extensive historical analysis of the shorelines using LiDAR and aerial imagery. This study enabled the team to identify how the shoreline has evolved over time, how these changes compare to present-day alterations, and the implications for archaeological sites.

Priority Areas

The project areas determined through the priority analysis are Hammocks Beach State Park in Onslow County, the Alligator River Game Land in Tyrrell County, and the Scuppernong River Section of Pettigrew State Park Dedicated Nature Preserve in Tyrrell County. Each has a unique cultural and environmental history.

Hammocks Beach State Park, Onslow County

Hammocks Beach State Park encompasses 33 acres along the Atlantic Ocean, Queens Creek, White Oak River, and Bogue Inlet. It includes a mainland area near Swansboro and three barrier islands. These diverse environments support a wide range of habitats, providing a home for various organisms including sea turtles, bears, marsh birds, and fish. As a chain of barrier islands, the park is particularly susceptible to the impacts of storm conditions and other oceanic changes.

The lands of Hammock Beach State Park have a rich history. Archaeological resources and indigenous stories indicate that American Indians utilized the islands for various purposes, such as fishing and hunting grounds. Notably, Huggins Island, a maritime forest located at the mouth of Bogue Inlet, served as fertile grounds for indigenous communities, leaving behind a wealth of evidence in the archaeological record. Following the contact period (c. 1600–1700 CE), colonists were granted land to settle in and around Hammocks Beach, leading to the establishment of plantations and other maritime industries along the shorelines.

When the Civil War broke out, portions of what is now the state park were used during the conflict. Both Bear Island and Huggins Island played crucial roles in the Confederate defense of this stretch of coastline. The Confederates established a six-cannon battery on Huggins Island and used Bear Island as a lookout point. These islands took on a similar military significance during World War II, this time for the U.S. Coast Guard, who utilized them as lookout points for German submarines.

Before World War II, Bear Island was purchased by a New York doctor, John Sharpe, in 1914, as a vacation spot. Following the war, Bear Island and the surrounding lands owned by Sharpe were donated to the North Carolina Teachers Association, the state’s organization for Black educators, in 1950. By 1952, the area became the state’s first and only park designated for Black Americans. The association established the Hammocks Beach Corporation to raise funds for facilities on the mainland. Over time, the group approached the state about converting the lands into a state park. In 1961, the park officially opened, serving as a dedicated space for Black Americans. Today, the park welcomes hundreds of visitors each year, eager to learn about the unique history and ecology of the area.

Alligator River Game Land, Tyrrell County

The Alligator River Game Land encompasses 24,440 acres on the south banks of the Albemarle Sound and the west banks of the Alligator River. While the reserve straddles U.S. Highway 64, the project area comprises the game lands north of U.S. Highway 64. This area is characterized by dense pine and hardwood forests, providing crucial protection for several endangered species and contributing to the conservation of pine forests in North Carolina.

Previously known as the Palmetto-Peartree Preserve, this section of the game land was established to safeguard the habitat of the Red-cockaded Woodpecker. Historically, it served as a hub for logging activities, with remnants of logging roads still visible across the property. Prior to large-scale logging, historical research indicates the presence of several plantations and fishing industries along the banks of the Albemarle Sound.

Established in 1999 under the guidance and funding of The Conservation Fund, the preserve was taken over by the NC Department of Transportation in 2015 after years of neglect and overgrowth. The NC DOT maintained the preserve as undeveloped land to support the conservation of woodpecker habitat. Ownership was transferred to the NC Wildlife Resources Commission in 2023. As conservation efforts for the woodpecker are still ongoing, the lands have been opened for hunting and integrated into the larger Alligator River Game Lands.

Scuppernong River Section of Pettigrew State Park Dedicated Nature Preserve, Tyrrell County

The Scuppernong River winds its way through Washington and Tyrrell Counties, eventually emptying into the Albemarle Sound. This river is protected as part of Pettigrew State Park, a vast state park spanning Washington and Tyrrell Counties showcasing the distinctive swamp ecosystems and rich history of the lower lands and waterways surrounding the Albemarle Sound. This area is the wintering habitat for tundra swans and boasts an extensive stretch of cypress forests, along with other unique flora and fauna characteristic of a pocosin ecosystem.

The Scuppernong River holds a long history of human use, intimately intertwined with the larger Pettigrew State Park and the nearby Lake Phelps. Functioning as a navigable waterway through dense swamps, the river was crucial for the Carolina Algonkians. After contact and colonization, the river became a primary transportation route for logs, crops, and other goods to and from markets along the Albemarle Sound. It connected interior plantations, including Somerset Place on Lake Phelps, to these markets through canals constructed by the enslaved community at Somerset Place.

Beyond Columbia, NC, the Scuppernong River remains largely undeveloped, presenting an environment reminiscent of that at the time of the Algonkians. As a transportation route, historical maps indicate the presence of shipbuilding yards, landing ports, and fishing activities along the river.

Pettigrew State Park was recognized as a state park status in 1947 following years of federal management and local calls for the establishment of a park in the area. In 2004, the park expanded its boundaries to include the Scuppernong River, thanks to a land transfer from The Nature Conservancy. This addition led to the creation of the Scuppernong River Preserve, a critical step in safeguarding the river and its shoreline from future development, while preserving its natural and unique pocosin ecosystem.

Sources

Agan, Kelly

2015, Hammocks Beach State Park. NCPedia. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Dease, Jared

2023, Pettigrew State Park. NCPedia. Accessed 6 November 2023.

Kozak, Catherine

2018, Palmetto-Peartree Preserve to Change Hands. Coastal Review. Accessed 6 November 2023.

North Carolina State Parks

2023, Hammocks Beach State Park. NC Division of Parks and Recreation, Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. Accessed 6 November 2023.

North Carolina State Parks

2023, Pettigrew State Park. NC Division of Parks and Recreation, Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. Accessed 6 November 2023.

OSA and AECOM completed fieldwork in the three project areas in 2024. In total, 248.6 miles were surveyed, examining 11 previously recorded sites, identifying 17 new sites and four potential sites, and recovering over 3,000 artifacts ranging from pre-contact lithics to historic ceramics to charcoaled wood and faunal remains.

Hammocks Beach State Park, Onslow County

When beginning the project, the team knew Hammocks Beach State Park contained several known sites within the park boundaries. These sites included pre-historic occupation sites, a Civil War fort, and historic homesteads. When planning for the survey, OSA and AECOM worked together to ensure that all site boundaries were defined and examined for potential impacts. The surveys focused on the main areas of the park, covering 429 acres and completing 811 shovel tests. Eleven previously documented sites were documented, and eleven new sites were discovered. Many of these sites were pre-historic occupation sites that showed extensive occupation from the Middle Woodland to the contact period. Following pre-historic occupation, there is a dearth of sites until the 19th and 20th century homesteads, infrastructure, and industrial uses of space. The team surveyed the submerged bottomlands. Unfortunately, no submerged sites were observed. Several of the sites show extensive erosion, including one that is already submerged and one that is losing 5 ft. of sediment annually.

Alligator River Game Lands, Tyrrell County

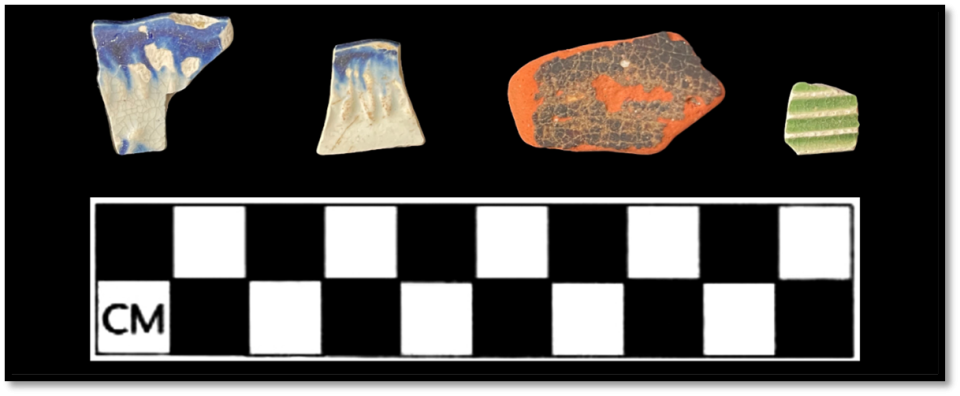

Work in the Alligator River Game Lands proved surprisingly interesting. Models showed the high potential for the discovery of new archaeological resources along the Albemarle Sound associated with homesteads and plantation sites. AECOM completed terrestrial surveys of sections of shoreline where defined shorelines and sandy beaches were accessible. Across the beaches, the team found six new sites. These sites all sat along the shoreline or stretched into the sound. The shoreline sites are all domestic artifact scatters dating from the 18th and 19th centuries. They contained artifacts, bricks, and glass fragments, hinting at long-term occupation. The two sites stretching into the sound were pound net piling sites. These sites are markers of a historic fishing industry in the area. Significant erosion is occurring along the Albemarle Sound, with the scatters suggesting that large portions of the homesteads they represent are now underwater.

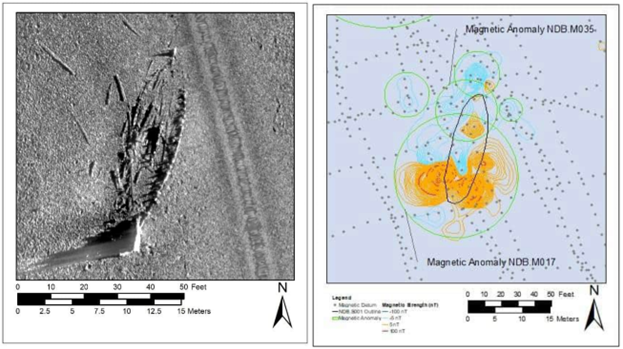

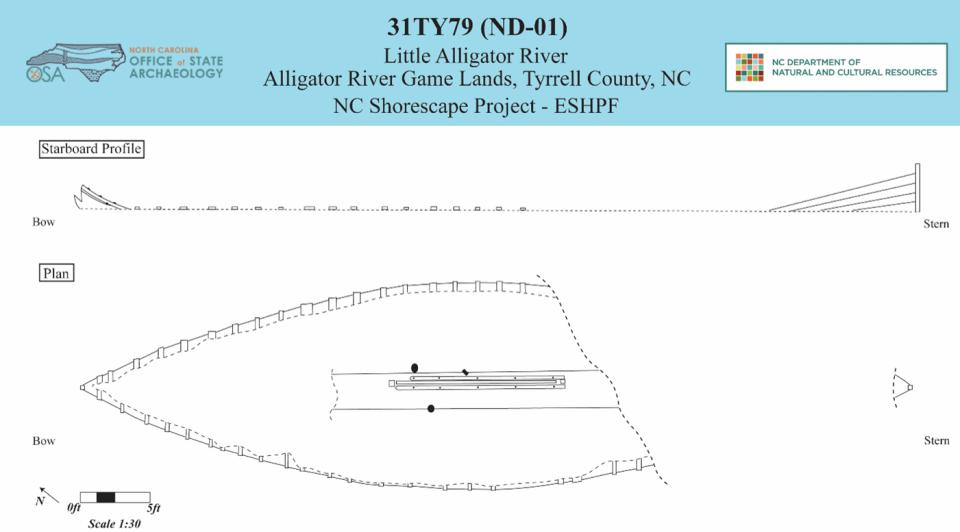

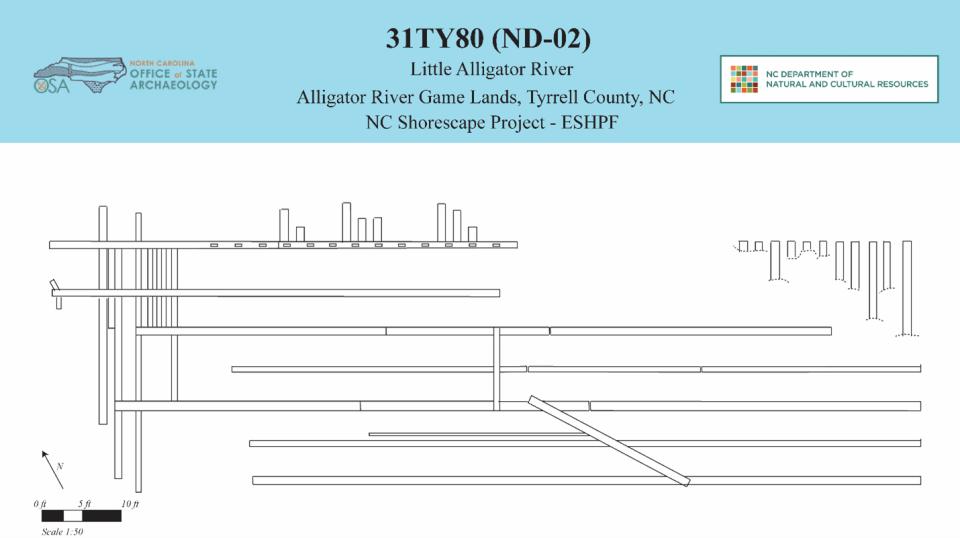

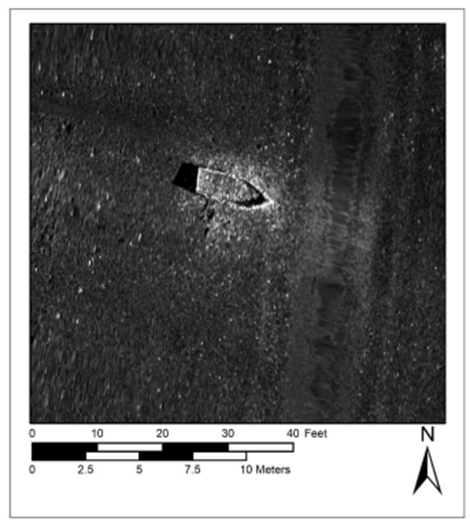

The AECOM team conducted an intensive submerged bottom survey around the main project area, including the Albemarle Sound, Alligator River, and Little Alligator River. The team discovered several submerged sites in the Little Alligator River. Two of these sites turned out to be shipwrecks, which were documented in greater detail by OSA in June 2024. One site is the remains of a 60 ft. wooden centerboard schooner. Much of the lower hull and centerboard trunk remain intact. Several artifacts were observed on the site, including a brick, a glass bottle, and a block from a block and tackle. This site is a traditional craft used in Coastal North Carolina, as several schooners have been observed throughout the region as a mode for coastal trade and fishing. The sizing on this vessel suggests that it was possibly built in the Albemarle region between 1830 and 1860.

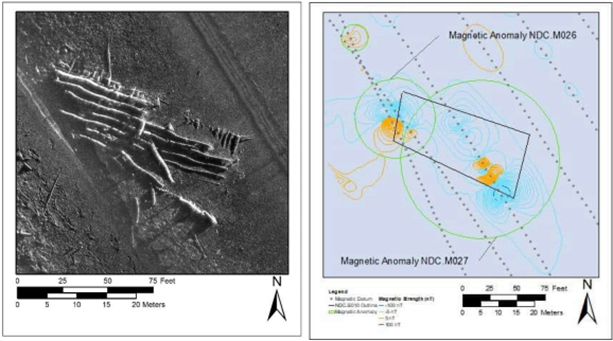

The second shipwreck is a large wooden barge, over 118 ft. in length. It has seven large longitudinal stringers, with one of the outer stringers notched with mortise holes. This timber would have supported a temporary outer edge. This shipwreck is a remnant of the lumber industry of Eastern North Carolina. In the Post-Civil War-era, Tyrrell County saw a boom in lumbering in the area, with the arrival of several companies, including Greenleaf Johnson Lumber Company, Branning Manufacturing Company, and John L. Roper Lumber Company. The John L. Roper Lumber Company set up operations along the Little Alligator River, as it provided access to the Atlantic White Cedar and Cypress forests. Cut timbers were loaded on log carts and hauled to the nearest waterway. From there, logs were rafted together to form log rafts fastened with log dogs. Further downriver, logs were loaded on to point barges for transfer to mills across the Albemarle region, including Deep Creek on the Dismal Canal, Gilmerton on the Elizabeth River, and North Landing on the Albemarle-Chesapeake Canal (Parkin 2019:21-22). The barges used in these operations are like this documented barge and it likely belonged to the John L. Roper Lumber Company.

Scuppernong River Section of Pettigrew State Park, Tyrrell County

Work in the Scuppernong River Section occurred in September, October, and December 2023. The swampy environment forced the AECOM team to reconsider methods for terrestrial surveys. The terrestrial team joined the underwater team to search for areas of defined shoreline. However, no defined shoreline was observed. The survey focused solely on surveys of the submerged bottomlands. Over the length of the river, the team observed a singular shipwreck site. The site is an approximate 12 ft long shipwreck with a squared stern.

Thanks to our partners AECOM, NC State Park, NC Department of Transportation, and NC Wildlife Resources Commission for their hard work and assistance in the completion of these projects.

This material was produced with assistance from the Emergency Supplemental Historic Preservation Fund, administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Department of the Interior.

This page was last modified on 09/24/2025